Two divergent views on the appropriate path for the cash rate got a good airing in the July Monetary Policy Board minutes.

- RBA Monetary Policy Board (MPB) minutes acknowledge that inflation is within target and likely to stay there, while monetary policy is ‘modestly restrictive’. The labour market was viewed as still tight, though subsequent data might imply this judgement needs to evolve.

- A majority of MPB members viewed holding rates steady as necessary to be consistent with strategy of being ‘cautious and predictable’. By contrast, the minority of members in favour of a cut highlighted downside risks to growth and inflation, as well as the lags in the effects of monetary policy. A 50bp cut was not discussed at all.

The minutes cleared up a few misconceptions that have been circulating, including about how the RBA sees the ‘neutral’ cash rate.

The July MPB minutes started by highlighting the surprisingly benign conditions in global financial markets. While the trade environment was still very uncertain, the more extreme scenarios now seemed less likely. There had been ‘little discernible effect’ on the Australian economy so far from the trade disputes. While it was judged that it was too soon to see any effect in the data, the minutes expressed some surprise that there was little effect in the sentiment survey data as well. The MPB put more weight than before on its base case that US tariffs would land at lower rates than originally announced, but still much higher than what prevailed before the current US administration was inaugurated. Understandably, though, there were concerns about whether markets were too complacent now, rather than simply overly pessimistic in April.

The discussion on inflation reflects the institution’s caution and understandable reluctance to declare victory on getting inflation back to target. While the monthly CPI indicator was deemed to be too volatile to rely on, the minutes highlighted alternative monthly calculations that ‘had not eased as much as the monthly trimmed-mean indicator recently’. All of this will be moot by the end of this year, when the full monthly CPI becomes available. As we have previously flagged, there is a risk that June quarter trimmed mean inflation comes in a little above what the RBA had forecast in May, and the RBA was happy to use the monthly data to highlight this risk.

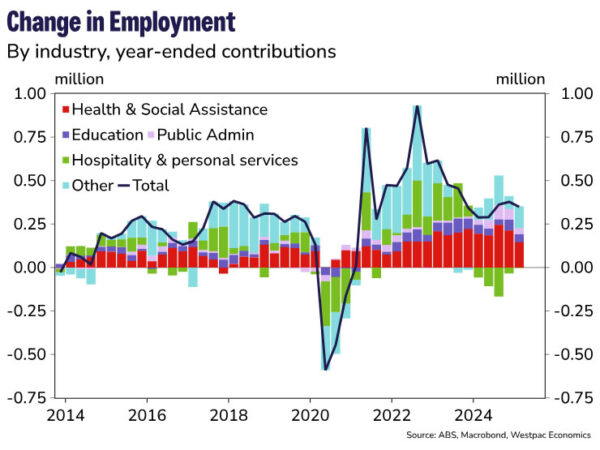

The RBA staff are alive to the need for a handover from non-market to market-sector employment growth, something we have been highlighting for some time. We take some comfort from the resilience of employment growth in most market-sector industries; an earlier downturn in hospitality-related employment now seems to have passed as well (see graph). Interestingly, the minutes suggested it was possible that a ‘shaky’ handover with slower employment growth could be compatible with an unchanged unemployment rate as long as the participation rate did not continue to trend up. Given the demographic trends underlying the participation trend, though, we are less confident that the net result will be benign for unemployment.

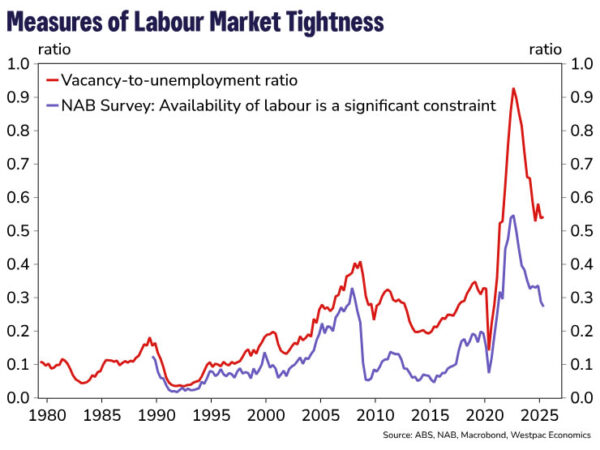

More broadly, the minutes elaborated on the RBA’s ongoing view that the labour market is still tight, pointing to the unemployment rate and underemployment rate. It can be reasonably inferred that the staff showed the MPB a graph of the vacancy-to-unemployment ratio along with the NAB survey’s measure of significant difficulty finding suitable labour, two series that are unreasonably tightly correlated given their different sources. Since the meeting, though, another reading of the NAB quarterly survey has come in, showing another fall. Together with the June labour force survey, this lends further weight to the idea that the labour market is again becoming less tight, after a pause in that unwind late last year.

The minutes again tackled the productivity debate, acknowledging that the expansion of the non-market sector and declining mining sector output had contributed to developments recently. These shorter-term factors are unlikely to continue at the current pace. While it is true, as the minutes highlight, that productivity growth has been lower in recent decades than over a long run of history, the IT/internet boom of the 1990s explains a large part of the gap. What the minutes do not make clear is whether the assumed pick-up in productivity growth in the forecasts is simply the unwind of the shorter-term factors – a reasonable assumption – or relies on AI boosting productivity similarly to the effect computers had in the 1990s.

The MPB also used this meeting’s minutes to clear up some misunderstandings about its view of the economy. In particular, the minutes included an extended discussion about the ‘neutral’ interest rate. A whole-economy view implied that monetary policy was ‘modestly restrictive’. Inflation was in the target and expected to remain around its midpoint even if the cash rate were reduced in line with market pricing at the time of the May forecast round. Various models from the academic and central bank literature point to a similar conclusion. Given the uncertainties around these models, though, ‘public discussion of the stance of monetary policy had possibly overemphasised the inferences that could be drawn from these alternative models, especially for the near term’. This admonition is in line with our earlier warning not to give that shift much credence. The average of estimates of neutral had fallen, but given that revision history, so would have the weight that policymakers put on that central estimate.

With a split decision, both the arguments to hold and to cut got a decent airing. The case to hold largely relied on some recent data coming in marginally stronger than the staff forecasts, along with receding risks of the more severe trade scenarios. The need for further confirmation that inflation was indeed on track aligns with a desire to remain ‘cautious and predictable’.

The minority of members who voted for a cut highlighted the risks that the growth and inflation forecasts might prove too optimistic. More immediately, and as we highlighted ahead of the meeting, they viewed the available information as already providing enough evidence that inflation was in target and on track.

A policy risk implicit in the minutes is that policymakers might cleave to a narrative about how they should conduct policy beyond its use-by date. A good-sounding phrase – ‘the narrow path’, say, or ‘not ruling anything in or out’ – starts off being useful, but it can shape thinking even when circumstances change. The ‘cautious and predictable’ language could be subject to this risk, especially if MPB members take it as an end in itself.

In any case, the argument for caution might not imply a slow return to neutral. The original basis for moving cautiously comes from William Brainard’s work in the 1960s. This showed that if you are uncertain about how much policy will affect the economy, you should do less in the face of a shock than you would if you were certain. But this means not going as far away from neutral as you would in a more certain environment. That is not the same as being away from neutral and returning more slowly than otherwise. But it does suggest that uncertainty about where neutral is will become a bigger issue for the MPB with time.